I cared for my father in the last few years of his life.

He suffered from chronic pain and the opioids he used to manage his condition impacted his mental health. He became more socially isolated, his sleep patterns changed, and he often fell asleep throughout the day. Eventually he had episodes of psychosis and his memory lapsed.

I cared for my husband through his battle with cancer.

His faith in a healing God largely overcame his doubts and fears about his condition, but when his cancer spread to his brain he dreamt of heaven and described revelations. Losing him to his psychosis was more terrifying than his cancer.

Caring for my dad inspired me to become a nurse. But it was less than a year after I graduated that my husband fell ill and I had to care for him too. Nursing at work, nursing at home. Caring at work, caring at home. Sometimes caregiving was deeply intimate and powerful, but there were painful moments. Nursing has long considered the patient’s mental health, but who was thinking about my mental health? There were times that I went to a dark place, or I felt my heart sink like a rock into my gut.

So my research attention turned from cardiac critical care and advanced heart failure to caring for caregivers. The people who sit in the corner while doctors talk and nurses take vital signs. The people who will be the only ones left to provide care when the patient goes home. The people who wonder, “How can I live without him?” And, “How can I live with her when she’s like this?”

I’ve thought a lot about how the health care system currently engages caregivers. Families and caregivers are considered a point of contact if the patient loses capacity or in the case of medical futility. But health care providers should ask if the caregiver has subtly started to take responsibility for the home. They should ask if a caregiver is stress eating or gave up time with friends to do the grocery shopping and laundry for two households. It may look like the family is handling things well, but beneath the surface adult children could be maxed out caring for the patient and often young children as well.

The PROMOTE Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, created in 2018, uses strengths-based approaches to improve person- and family-centered care. Right now I am leading CAREGIVER-Support, a pilot study that asks advanced heart failure patients and caregivers:

- What are your needs at home?

- How do you prioritize complex symptoms and medications?

- How do you interact with multiple providers?

We’re using this information to develop an intervention that improves caregiver quality of life and lessens their sense of ‘burden’. The intervention will ask four questions:

- How can we help you describe who you are and your life’s purpose? Can we frame your experiences as a caregiver as a part of that greater purpose?

- Can we help you connect to existing services that could provide financial or caregiving support in the home?

- Can we help you think about your community and social network and ways to engage them to support you?

- What is one small goal we can work on together to improve your quality of life?

This work is just beginning. We are bringing together people with diverse perspectives to ensure our intervention is useful, thoughtful, impactful, and even brings caregivers and patients joy. Our social design fellow from MICA will help us develop creative intervention activities that go beyond a survey and a checklist. Patients, caregivers and providers will be at the table talking through each step. And yes, there are also seats for brilliant scientists who will help us keep track of measurable outcomes so we can see how we’re moving the needle.

Part of my motivation is that I want my own caregiving experiences to have meaning. But as a nurse, I know that holistic care means caring for caregivers and families because they will be responsible for so much hidden health care. Holistic care, for patients, families, and caregivers, is my greater purpose.

May is Mental Health Month

Learn more:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: MARTHA ABSHIRE

Martha Abshire, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She is currently developing an intervention to support caregivers of advanced heart failure patients through a grant funded by the PROMOTE Center. In addition, Dr. Abshire is a collaborator on the PRECURSORS study, examining end-of-life decision making in a large cohort study of Johns Hopkins physicians.

Martha Abshire, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She is currently developing an intervention to support caregivers of advanced heart failure patients through a grant funded by the PROMOTE Center. In addition, Dr. Abshire is a collaborator on the PRECURSORS study, examining end-of-life decision making in a large cohort study of Johns Hopkins physicians.

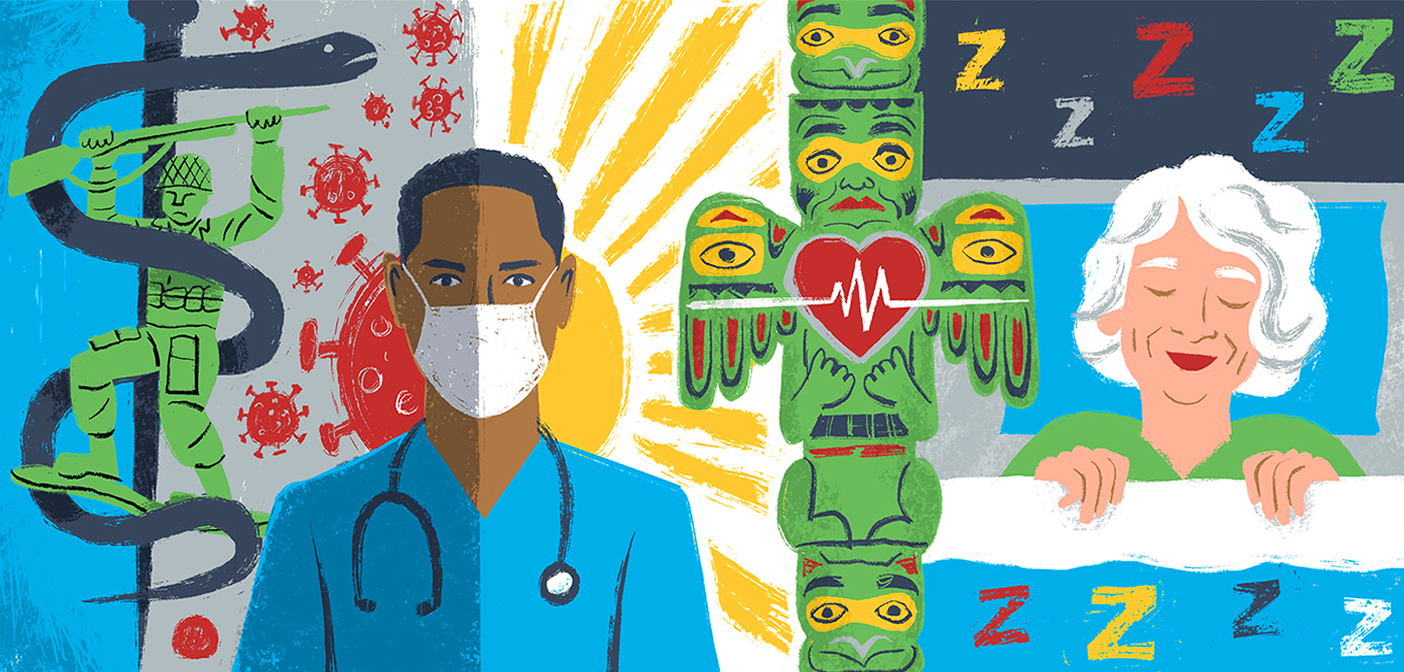

The Returned Peace Corps Volunteer to Nurse Pipeline

The Returned Peace Corps Volunteer to Nurse Pipeline JHSON Highlights

JHSON Highlights Heart Health in Native Populations

Heart Health in Native Populations COVID and Nursing: Where to from Here?

COVID and Nursing: Where to from Here? Summer Research Roundup 2023

Summer Research Roundup 2023