In the emergency room, one of the few things that can move faster than even the most highly skilled care team is a preconceived notion. Left unchecked, any such judgments or assumptions—even subconscious—can and do hurt care.

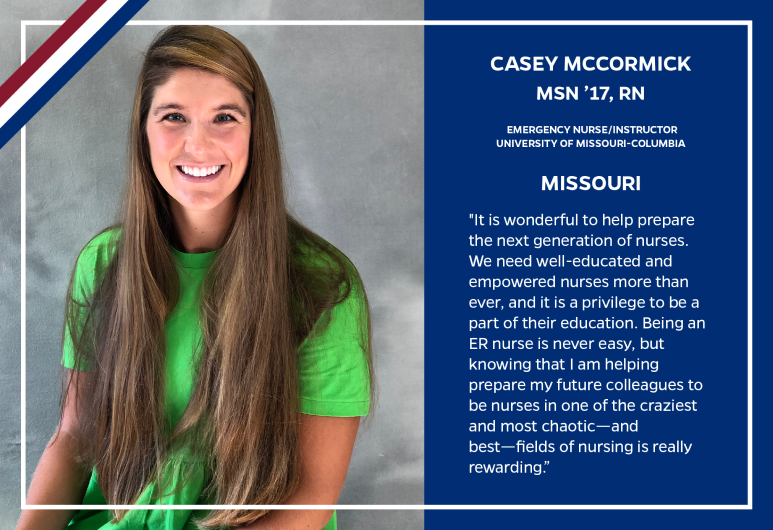

It’s something Casey McCormick, MSN, MPH, RN, of the University of Missouri-Columbia has seen time and again. While earning a master’s degree in public health, McCormick had worked with the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition, visiting “shooting galleries,” places where intravenous drug users gather to inject narcotics, as part of an evaluation of a new law meant to save lives by not prosecuting fellow users who called in overdoses. It was an off-putting and eye-opening experience for the Charlotte, NC native.

Today in Missouri, when she encounters substance users in the emergency room, McCormick can sense what they’re thinking and why they may display a bit of attitude: “They tend to be the most difficult patients because they think everybody is judging them. ‘This is your fault. You shouldn’t use drugs.’ ”

These are people who need help, period. “Much of what we do in the ER is harm reduction. We’re the safety net when things have failed,” McCormick explains of “societal problems vs. ‘emergencies,’ so to speak.”

“We need to go into it with a harm-reduction mentality. My job here is not to judge the behavior you’re doing but to keep you safe.” Such an approach, she says, “helps you get through to these patients. It actually makes your job easier. … It has helped me to see people and patients who are going through this as more than their disease. It gives you a lot of empathy in a place—the ER—where sometimes empathy is not a priority.”

It’s the same approach McCormick tries to use with any ER patient, take for example athletes injured on the field of play and perhaps under pressure to get back out there, something she knows plenty about. “It’s just reminding them in an emergency that they matter more than their sport or their injury. ‘We’re going to do everything we can to get you back. But right now we need you to be safe and healthy. You’re going to be OK.’ Focus on that first.”

She’s been there, as a former high school and college soccer player with four separate knee surgeries under her belt. “I don’t think anyone had ever talked to me that way.”

Now as a full-time instructor as well as a part-time ER nurse at University of Missouri Health Care, McCormick stresses these lessons with an extra dose of humility, some of which was hammered home by preconceived notions of a very different sort that she encountered while working in Madagascar. McCormick was a part of a team—consulting on a hygiene project designed by and for villagers—yet she was still so … apart. “It wasn’t just me showing up and saying, ‘This is what you should do.’ They just needed consulting on monitoring and evaluation, grant requirements, evidence-based implementation stuff.”

“I looked like no one,” McCormick explains. “I didn’t speak the language.”

Yet she was treated as an all-knowing visitor.

“Oh, this American, this Westerner, she must really know what she’s talking about. It made me uncomfortable. I hadn’t earned any of that respect. They were just automatically giving it to me because of where I came from and what I looked like. It forces you to be very thoughtful about how you act and what you do. It was a very humbling experience.”

There was a funny side effect, though, and it’s one of the reasons why McCormick today is part of the United States of Nursing.

“I would go into the community, and we wanted to alleviate disease burdens and things like that. So they thought, ‘Oh, you must be a health care person. You must have clinical experience. Can you help me with this cut I have on my foot?’ It was, like, ‘No, I cannot.’ It made me feel inadequate: ‘If I’m going to be teaching people on how to be healthy, I should also be able to help them do that. I need some clinical skills if I’m going to continue doing this.’ ”

“So that’s where my path to nursing really started, in a very, very small village in Madagascar.”

It continues in the classroom, where McCormick can share rich stories with the first-year nursing students. She’s been in the shooting galleries, she’s been under the knife, she’s been judged for good and, OK, maybe too good, and if she hasn’t seen it firsthand or doesn’t know, McCormick says so. “I tell them, I am not that far off from where you guys are sitting right now. We’re never going to know everything.”

A lot of what she does know McCormick learned at Johns Hopkins, of course. “I had some really cool clinical instructors, probably the age I am now, so maybe five or six years older than I was. They were so happy to be educating that it made me excited to be there. I would think, ‘Maybe one day I can be one of those cool nursing instructors to other students.’ ”

She was also fortunate to be singled out by a seasoned, no-nonsense, “awesome” preceptor at her first job—with University of North Carolina Health Care—who’d spied her resume and wanted to see for himself whether a Hopkins Nurse was really all that. “He taught me that saying ‘I don’t know’ is actually far more efficient and better for your patient than trying to fake that you know something.”

McCormick now passes that ethos on to her own students: “I would rather have a nurse like that than have them be dangerous and think they know everything.”

The students give plenty back. Perspective, for instance. “That’s kind of why I went into teaching in the first place. I had been burning out a little bit at the bedside. Students are still so excited to be nurses. They really want to do this job.”

So McCormick brings them her tales from the ER. (“I can tell a story about whatever we’re discussing in class. We’ve seen it all.”) Boiling down nursing to its fundamentals for them in clinicals makes things even more clear to McCormick. (“It’s, ‘Wow, if I only thought about that in such a simplified way at the bedside.’ It doesn’t always have to be so complicated.”) And she can walk back to the ER refreshed and refocused.

“It reminds me: ‘You do know how to be a nurse.’ ” — Steve St. Angelo

Birth Companions Talk Doulas and Maternal Health with Mayor Brandon Scott

Birth Companions Talk Doulas and Maternal Health with Mayor Brandon Scott Earth Day: An Opportunity to Address the Environmental Injustice of Plastic Pollution

Earth Day: An Opportunity to Address the Environmental Injustice of Plastic Pollution Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health?

Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health? No. 1 Rankings for the School of Nursing and a Pipeline to the “Best Jobs”

No. 1 Rankings for the School of Nursing and a Pipeline to the “Best Jobs” Global Service Learning: Guatemala

Global Service Learning: Guatemala