Each November, Native Americans become the center of a national myth – the Thanksgiving myth. President Abraham Lincoln originally proclaimed the holiday at the height of the Civil War to “heal the nation”, neglecting to acknowledge or discuss the numerous forms of violence Indigenous Peoples have endured for centuries due to colonization and assimilation practices.

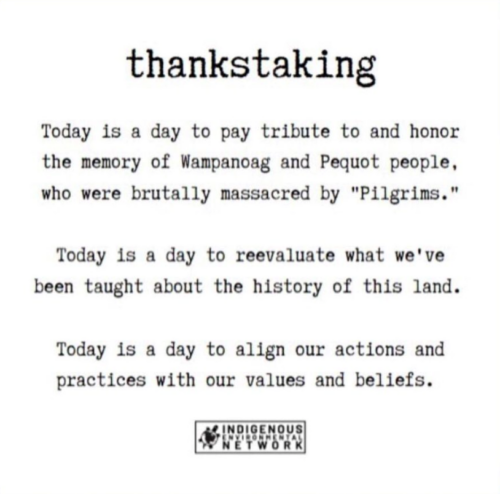

Considering the upcoming holiday, #Thankstaking – the Native-influenced alternative to Thanksgiving – has gained traction to highlight issues like land theft, exclusion of critical history in schools, and removal of Native Americans – particularly children, in the form of Residential Boarding Schools.

Here is what you [likely] did not learn about the Boarding School era and how you may consider [read: should] celebrating the upcoming holiday more mindfully:

In 2021, Archeologists Detected 200 Unmarked Graves at an Old Residential School in Canada

Eradication of cultural identity and peoples through reeducation is not an uncommon form of violence against an ethnic group. Between 1883 and 1998, the government forcibly took 150,000 Indigenous children and placed them in residential schools throughout Canada. Funded by the state and run by churches, these schools were designed to “civilize” Indigenous children through assimilation and Christianization by stripping them of their culture and community. The first boarding school in the United States, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, opened in Pennsylvania in 1879. Their motto: “Kill the Indian, save the man,” was later adopted by the Canadian government. Curricula consisted of domestic and manual labor and prayer. If children tried to speak their language or practice cultural traditions, they were punished. Dehumanized and perceived as savages, children were physically and sexually abused by church members. By 1920, the Indian Act made it mandatory for every Indigenous child to only attend residential school. More than 3,000 children died in Canada alone either from 1) abuse, if they tried to escape and were captured, or 2) diseases like tuberculosis, malnutrition, and poor sanitation. Schools had their own cemeteries, and children were responsible for digging their peers’ graves. It was more cost effective to keep the deceased children buried on school ground than to send them back to their families – i.e., parents were often not informed that their child had even died. It was not until 2015 when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded that a cultural genocide had been committed against Indigenous Peoples.

Shedding Light on Injustice and Trauma Through Advocacy

After this most recent discovery in Canada, the question remains: What has not been uncovered and/or acknowledged still in the Unites States? Between 1819 and 1969, the system in the U.S. consisted of 408 federal Indian boarding schools across 37 states/territories. To date, the U.S. is the only nation that has not formally acknowledged crimes committed against Indigenous Peoples and the federal government has blatantly disregarded numerous treaties, which include the promise of health care, safety, and protection made in exchange for the land that we all live, work, and play on today. But, despite it all?

Native Americans and Indigenous People are Still Here

In June 2021, Secretary of the Interior and enrolled member of the Pueblo of Laguna, Deb Haaland, introduced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative – a big step towards acknowledging the unjust legacy of the Boarding School era and addressing historical and intergenerational traumas still pervasive today.

We cannot turn back time. This history is woven into the fabric of our global community, and these experiences are still felt by our Indigenous colleagues, neighbors, and friends today. As a nursing community, we must reckon with these issues, speak truth, and lead in advocating for impactful change.

- Read and learn about what really happened during the three-day feast in 1621 between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoags

- Learn about ways you can be a critical ally for and to Indigenous Peoples

- Support and promote Native-owned and Native-led businesses and initiatives

- Speak up and challenge systems that have [and, in cases, still do] socially excluded Indigenous Peoples and made them feel invisible

About the Authors

Katie Nelson, MSN, RN, is a PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. Her research focuses on principles of justice and equity in serious illness care access and delivery among Native American communities.

Mumtahana Meah, BS, is a student in the Masters—Entry to Practice program and a Research Honors Program scholar at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. Her research interest includes the influence of cultural traditions and spiritualty on hospice and palliative care within marginalized communities.

Meet APANSA, the Asian Pacific American Nursing Students Association

Meet APANSA, the Asian Pacific American Nursing Students Association Birth Companions Talk Doulas and Maternal Health with Mayor Brandon Scott

Birth Companions Talk Doulas and Maternal Health with Mayor Brandon Scott Earth Day: An Opportunity to Address the Environmental Injustice of Plastic Pollution

Earth Day: An Opportunity to Address the Environmental Injustice of Plastic Pollution Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health?

Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health? No. 1 Rankings for the School of Nursing and a Pipeline to the “Best Jobs”

No. 1 Rankings for the School of Nursing and a Pipeline to the “Best Jobs”