When a baby’s life is cut short, where do families turn?

By Susan Middaugh

Three days after her twins were born prematurely in 2009, math teacher Kitty Goffaux learned that Tommy and Ashley had a rare genetic disorder called Zellwegers Syndrome. Their prognosis—a life expectancy of less than a year—was stunning for Kitty, who had com-pleted her third and final attempt at in vitro fertilization.

Kitty credits Mary Peroutka, BSN, RNC-OB, clinical nurse III, founder of the hospital’s Rising Hope Perinatal Hospice Program, with supporting her and her husband Jaime’s decision to care for the twins themselves after three weeks in the NICU at Howard County General Hospital.

“Without her program, we would have been unable to bring them home as soon as we did or maybe not at all,” said Kitty. Their attending physicians were concerned that the babies, who had multiple health problems, were too fragile to be outside the hospital. “Mary advocated with the doctors and made sure we were comfortable with the training we received from the NICU nurses,” she said.

The Goffauxes are one of more than a dozen families that have participated in Rising Hope since the program began last year as an outgrowth of the hospital’s Perinatal Bereavement Program. Some, like Kitty, know their pregnancy is at risk but a specific diagnosis is missing. Other women are aware through genetic testing that their fetus has a fatal condition, but they choose to continue their pregnancies anyway.

“These families need support during a difficult time,” said Peroutka, a 20-year veteran of HCGH’s labor and delivery unit. “It’s so important to the family’s individual healing and to the mental health of our community.”

The Horizon Foundation in Columbia agreed—in the form of a one-year $19,950 grant to cover administrative costs. “I can’t imagine a more compelling need than the one this program addresses,” said Richard Krieg, PhD, Horizon’s president and chief executive officer.

Rising Hope, the first hospice program of its kind in Maryland, offers its services free of charge. Peroutka says her primary role is to listen and later to assemble a team of hospital professionals to help with their emotional or spiritual needs. Her ability to coordinate a prompt response is critical. “The parents may only have minutes to whisper in their baby’s ears to tell them how much they love them,” she said.

She may also help the family create a birth request list in advance of delivery, perhaps arranging a baptism or for siblings to be present in the delivery room.

Afterward, she follows up with each family for a year, often by phone or in person. Tommy Goffaux lived for nearly six months and his sister, Ashley, for 11 weeks. “Mary was at our house when Tommy died,” Kitty Goffaux said, and she’s still dedicated to the family’s needs, “troubleshooting with our insurance company over the twins’ medical bills.”

Organizing a Perinatal Hospice Program

- Hospitals that want to start a similar program may benefit from Mary Peroutka’s experience:

- Identify a local need.

- Talk to the hospital’s CEO and ask for executive and board support.

- Put your proposal in writing.

- Find community partners to fund the program.

- Build a team of medical and spiritual professionals from within the hospital.

- Reach out and educate local obstetricians and pediatricians about the services available to them and their patients.

- Be prepared to raise money when grant support runs out.

Questions? Contact Mary Peroutka at (410) 884-4709 or [email protected].

JHSON Highlights

JHSON Highlights The Knowledge to Embrace Life

The Knowledge to Embrace Life Death and Dying, with Cultural Humility

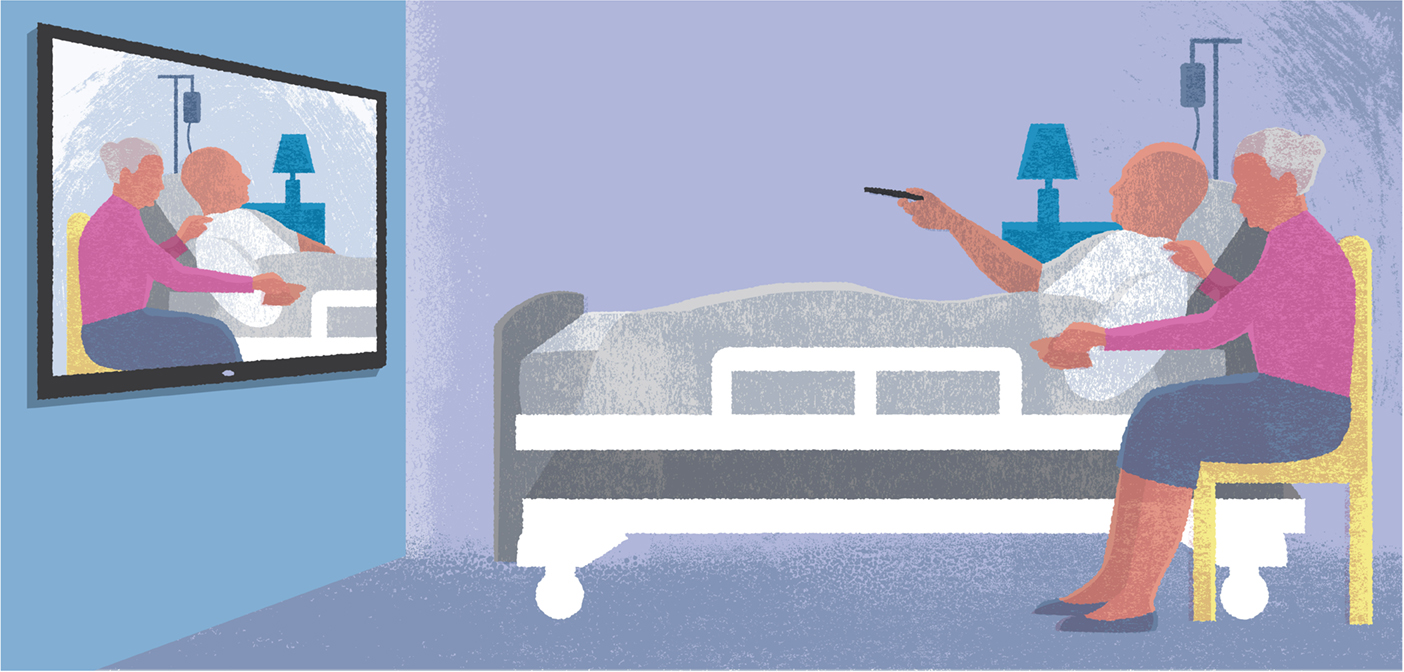

Death and Dying, with Cultural Humility Dramatic Impact of ‘Telenovelas’ on Hospice Care

Dramatic Impact of ‘Telenovelas’ on Hospice Care Nurses and Genetics and Genomics

Nurses and Genetics and Genomics