Written by Kamila A. Alexander, Rebecca Goldberg, Margaret Eddleton, & the TANGLED Research Study for Young Women Team

“Research causes harm.”

“Research takes from our community and never gives us anything back.”

We often consider these sentiments when discussing the best ways to conduct research with Black women. The legacies of medical injustices done to Black women in the name of research—“gynecological breakthroughs” discovered through experiments on Black female slaves and children, to Henrietta Lacks, to modern racism in the health care system and beyond—loom large over the research enterprise.

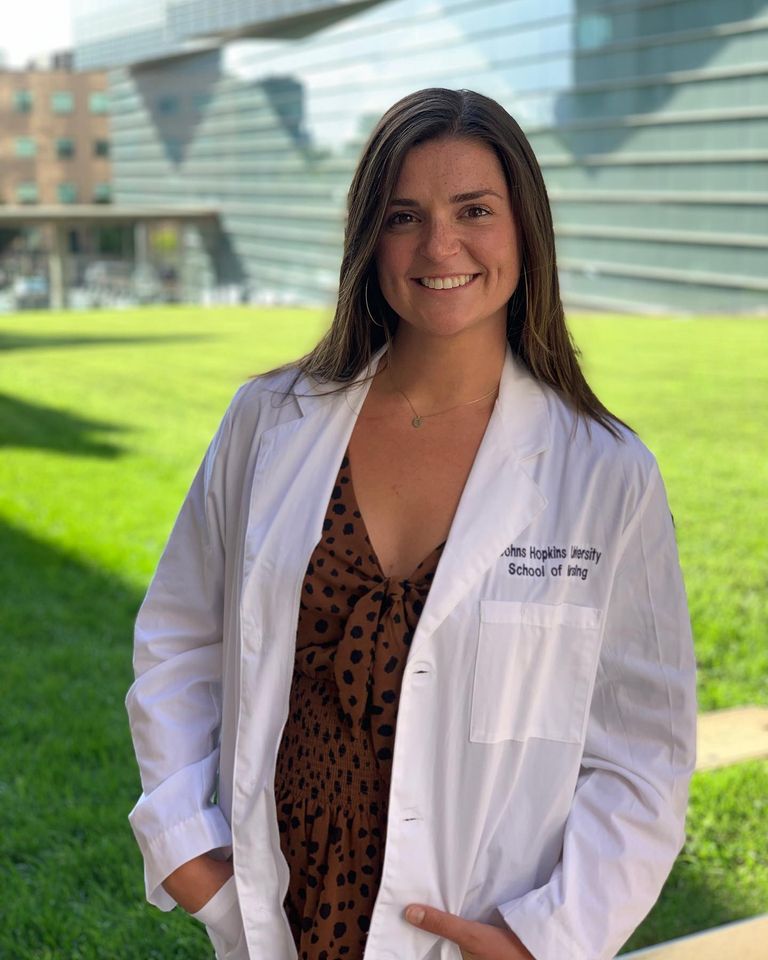

These tensions are especially challenging for Kamila Alexander, PhD, MSN/MPH, RN, assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing to navigate. She leads the TANGLED Research Study for Young Women, and happens to be a Black woman scientist. The study connects with women experiencing intimate partner violence to explore how their social networks might influence their health behaviors, including preventive strategies for safety that promote general well-being. And yet…

“I often ask myself if there are any positive effects of conducting research with Black women, especially those who face vulnerabilities and danger in their intimate relationships.” she says.

But Tangled has found that research participation is having dual results: enabling young women to reflect on their experience and educating them about healthy relationships.

Here’s what participants are saying:

“It felt good talking about things I haven’t talked about.”

“It was cool, different, and I stepped out of my comfort zone.”

Study participants are young Black women, aged 16-24, who have recently experienced intimate partner violence. Conversations during research participation have helped them understand which behaviors are classified as IPV or abuse, and provided new language, frameworks, and tools to evaluate IPV experiences in their own lives. For many of them, this is a new dialogue for experiences they have never shared. What’s more, their reflections illustrate the possibility for an unorthodox yet critical role that research can play in reforming our approach to preventing systemic violence and abuse: diffusing the awareness that violence is not a natural part of life, and sharing the tools to address it, throughout that person’s community and social networks.

Research can play an unorthodox yet critical role in reforming our approach to systemic violence: diffusing awareness of violence and the tools to address it through participants’ networks.

In fact, several participants talked about their participation as an opportunity to do something for other women. “I would like you to use it [information from the research] to help other people who are like or unlike me to find peace and clarity…to find strength in themselves,” one woman said.

We can’t ignore that violence is a leading cause of death among Black women, that, when violence is the cause of death, they are most likely to die at the hands of an intimate partner, and that almost three in four women who report experiencing IPV in their lifetimes report it happens before the age of 25. Research can play an essential role in Black women’s health broadly, and more specifically in supporting IPV survivors and spreading resources to the community.

In TANGLED, the research itself is a positive intervention. For example, the study praises Black women’s strength and survival when facing trauma due to IPV; “Black women bring many strengths and so much resilience to intimate relationships, and I wanted to build a strengths-based program of research that magnifies these stories,” Dr. Alexander says.

Further, researchers use trauma-informed data collection techniques that help women find comfort when discussing painful experiences and build trust between patient and researcher. For participants, research studies can be a key turning point for education, behavior change, and positive future orientation, which are all critical for overall well-being.

So where do we go from here?

In intimate partner violence and beyond, we know that research creates an opportunity to provide education, resources, and empathetic listening. We also know that our community’s health is profoundly shaped by social interactions and personal relationships. And finally, we know that it is the research community’s moral and ethical responsibility to focus more resources than ever on sustained research and interventions for marginalized populations to achieve health equity.

This blog is a part of the “Dialogues in Health Equity” series by the Health Equity Faculty Interest Group. They are committed to decreasing health disparities experienced by local and global communities by promoting social justice and health equity through nursing practice, research, education, and service.

Read more:

- Programs to Transition Pediatric Patients with Sickle Cell Disease to Adult Care are Few and Far Between

- Undocumented Latinos Need Access to Care Too

- We Need Culturally Appropriate Resources When Latinas Experience Intimate Partner Violence – The “Invisible Crisis”

- Can you hear me now?

- Henrietta Lacks: Rendering the Invisible, Visible

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: KAMILA ALEXANDER

Kamila Alexander, PhD, MPH, RN is an Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She uses health equity and social justice lenses to research the prevention of sexual health outcome disparities and the complex roles that structural determinants such as intimate partner violence, societal gender expectations, and limited economic opportunities play in the experience of intimate human relationships. Dr. Alexander is the co-leader of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing Health Equity Faculty Interest Group.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: REBECCA GOLDBERG

Rebecca (Bea) Goldberg is an MSN (Entry into Nursing) candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, and a research assistant for the TANGLED study. Previously, she earned dual bachelor’s degrees in Anthropology and Art History at the University of California, Santa Cruz. After graduation, she worked for the university abroad as a researcher in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Her interests include sexual health, harm reduction, and health equity. Bea aspires to become a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner and work with children in underserved communities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: MARGARET EDDLETON

Margaret Eddleton is an MSN (Entry into Nursing) candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She received her Bachelor’s degrees in both Chemistry and Biochemistry from Virginia Tech and now works as a Research Assistant on the Healthy Relationships Team and as a Birth Companion. Margaret’s interests include working to address health disparities through community-based approaches, with an emphasis on the the social determinants of health. She aspires to continue learning and one day be a provider in the nursing field.

You’re Welcome

You’re Welcome My First Teachers in Nursing School Weren’t Nurses

My First Teachers in Nursing School Weren’t Nurses Episode 31: From Erasure to Empowerment

Episode 31: From Erasure to Empowerment Doing Right by Minority Veterans

Doing Right by Minority Veterans 20 Questions with Associate Dean of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging, Dr. Jermaine Monk

20 Questions with Associate Dean of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging, Dr. Jermaine Monk