Written by Steve St. Angelo

Curbside Injection Clinics offer patients ‘drive-thru’ care with a side of COVID safety

On a hot, late-summer day, Lori Parker, oncology RN, is calm and cool in scrubs, surgical mask, and face shield, dragging two mobile carts at once out to meet a cancer patient’s car in the traffic circle of Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Skip Viragh Building. She checks him in using a wristband and bar-code scanner and pulls up his chart on Epic, the electronic medical record system. He’s a first-time user of a curbside injection program that allows patients concerned about COVID-19 exposure—or at risk due to compromised immune systems—to be treated without ever leaving their cars. In 15 minutes or less, they are rolling on their way.

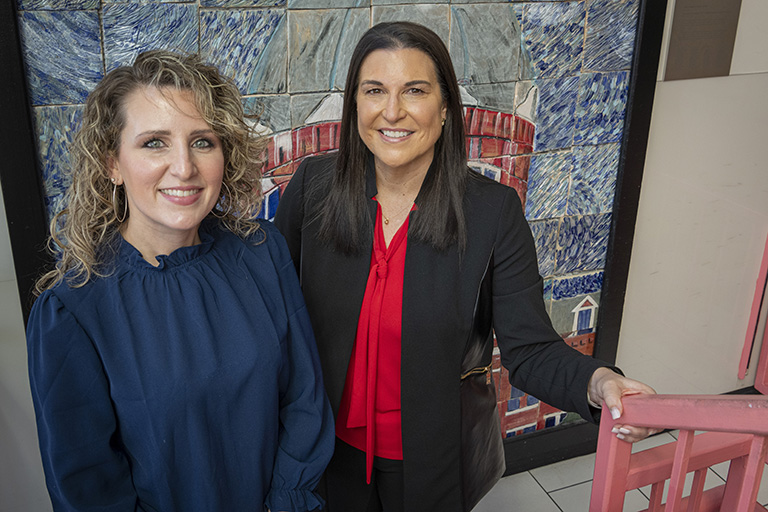

Since April, more than 1,500 patients have utilized Viragh’s Curbside Injection Clinic and a companion site across Orleans Street at Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Weinberg Center, according to MiKaela Olsen, DNP, APRN-CNS, FAAN, an oncology and hematology clinical nurse specialist and the driving force behind the service. Health care centers nationwide have taken notice, calling Olsen and her team for advice on setting up their own versions of the clinics.

We had to adapt to the circumstances and come up with a way to get [patients] the care they needed while also protecting them from becoming infected with the coronavirus.

“Patients were afraid and were canceling appointments for important care,” explains Olsen of the impetus behind the sidewalk service. “We had to adapt to the circumstances and come up with a way to get them the care they needed while also protecting them from becoming infected with the coronavirus.” A former Army nurse and an inexhaustible innovator, Olsen drew on her experience with field hospitals to focus on rapidly building an outdoor program that could match the level of quality care on the inside—and then recruit nurses who were battle tested.

Parker was among those hand-picked for the role. And on this day, she is showing why, fielding phone calls from patients on their way to the drive-up, spacing out the arrivals as she preps for the next one. She hustles in and out of the sliding glass doors to meet each vehicle, muscling the carts across the pavement, treating each new patient like the only person in the world.

It’s like clockwork, mostly, until another first-timer stomps angrily up to her station. He has misunderstood how the operation works and has been waiting impatiently for treatment … over in the parking garage. Parker doesn’t blink or hesitate at his indignation, whisking him into a dedicated side room for treatment on the spot: one more happy—or at least happier—and now better-informed customer. “She’s a problem-solver,” explains Olsen. The side room is generally reserved for gluteal injections or other treatments that might leave patients feeling too exposed even in their vehicles.

Viragh and Weinberg treat different types of cancers, those with solid tumors presented by pancreatic or prostate cancer, for instance (Viragh), or “liquid” tumors (from leukemia or lymphoma) at Weinberg, where a sidewalk scale tracks a patient’s weight, which can affect dosages. At Weinberg’s injection clinic, where the emphasis is more on chemotherapy, Olsen chose hematologic malignancy RNs Joanna Bautista and Erica Langton as champions. What could at times be a lengthy appointment for labs and a chemotherapy injection has turned into a 30-minute drive-up visit. Nurses complete a full assessment, take vital signs, and do some teaching before administering the chemotherapy.

Patients love it, and some say they don’t ever want to go back to being seen in the cancer center. We plan to keep both [indoor and curbside clinics] going after COVID-19 is over.

At the curbside oncology clinics, patients may have blood drawn and receive injections of therapy drugs, growth factors, or vaccines and have their vitals checked without ever leaving the car, or whatever vehicle brought them. “We’re in an inner-city area, and people sometimes show up for treatments in Ubers and taxis,” Olsen says. “Patients love it, and some say they don’t ever want to go back to being seen in the cancer center. We plan to keep both [indoor and curbside clinics] going after COVID-19 is over.”

Parker loves the constant action, the variety of patients, and the freedom of being outside the hospital for part of each shift and says she doesn’t worry about the approaching winter, or whatever weather comes. “Except the wind. That’s the worst,” she says. The medicines are likewise weather-proof, with those that require refrigeration kept in a “smart” cooler that alerts the pharmacy should temperatures rise. And a security detail makes sure supplies don’t walk away and that nurses work worry-free.

At both clinics, other common outdoor services include flushing central line catheters and performing dressing changes. “We’re still thinking of ways to treat more things curbside,” says Olsen.

COVID and Nursing: Where to from Here?

COVID and Nursing: Where to from Here? Summer Research Roundup 2023

Summer Research Roundup 2023 All Together Now!

All Together Now! Help on Diabetes in Schools

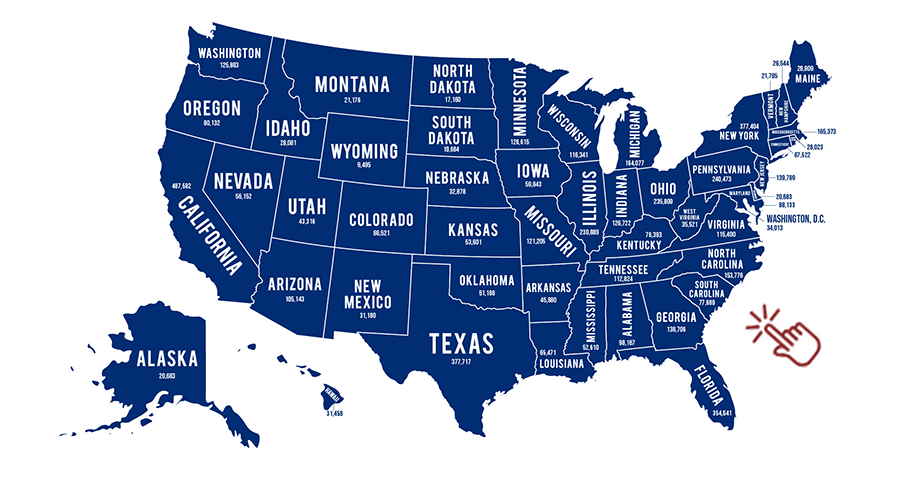

Help on Diabetes in Schools 50 States, 50 Stories, 50 Reasons Why

50 States, 50 Stories, 50 Reasons Why