My grandfather, a 75-year-old African American man, visited his primary care provider for his yearly checkup. The provider said, “You are a 75-year-old black male and you have not been diagnosed with hypertension. How is that so? You must have a strict diet.”

As a soon to be nurse, I ask, “Why did his doctor assume that because he is African American he would have hypertension?”

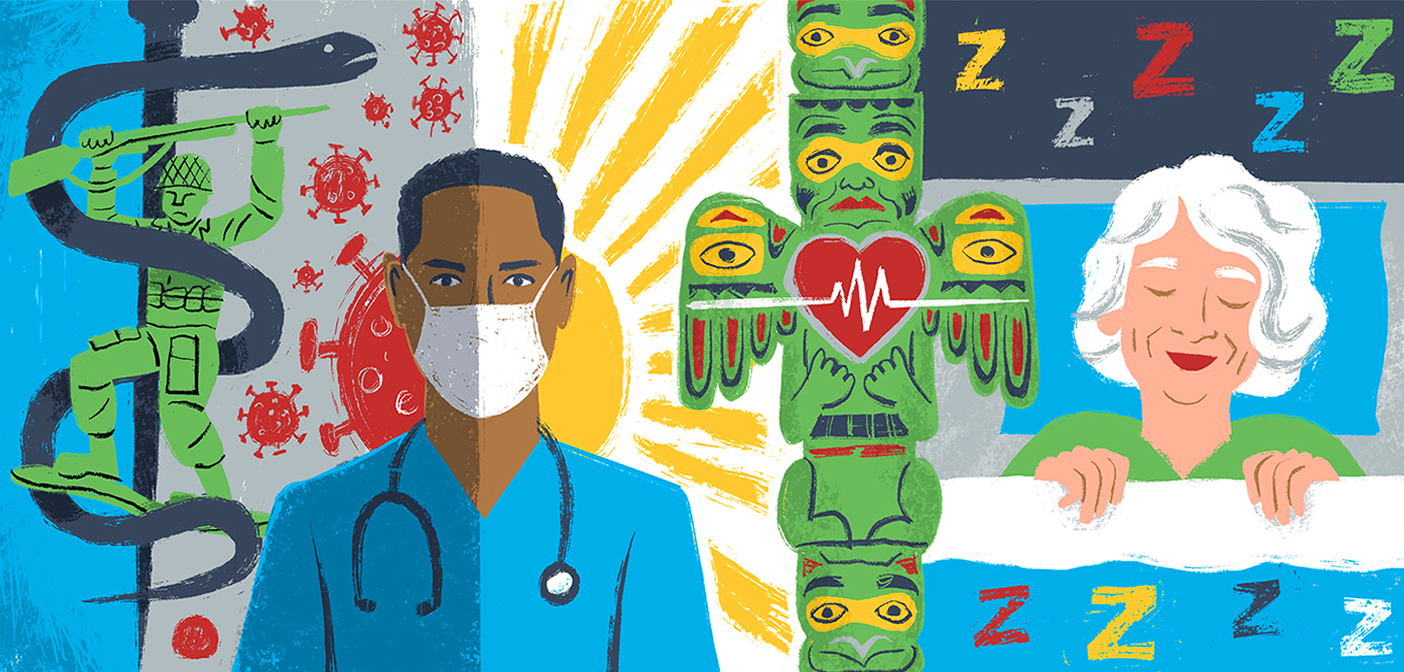

I think back to a lot of my lectures, where being African American or black was described as a risk factor for heart disease. Yet new research from Dr. Diana Baptiste and Dr. Yvonne Commodore-Mensah confirms what we already felt: although African Americans have a higher risk for heart disease, race alone is not an indicator. Environmental, psychological, and social factors may play a larger role.

Risk factors are behaviors, conditions, and characteristics that makes a person more likely to get a disease. People can be at risk regardless of race because of a variety of stressors—for example, they may struggle to provide for their family or lack access to health care. So that could apply to a white person experiencing the stresses of poverty, but not an African American person who is middle class and does not experience that kind of stress. However, racism itself can be a psychological stressor with physical effects. And it impacts people of underrepresented racial or ethnic backgrounds across the lifespan and across socioeconomic strata.

From Dr. Diana Baptiste:

Although African Americans have a higher prevalence of heart disease, race alone does not contribute to these risks. Cultural and genetic influences, along with social factors such as wealth and employment, marital status, how people are educated and where they live and work can affect risk for heart disease, as well as how it is managed, and ultimately health outcomes. We need to acknowledge how these social factors impact our patients and incorporate these considerations in their care and in our training of health care professionals.

It’s depressing to hear over and over that your race determines your health outcomes. It makes nursing school harder when I and other students from underrepresented racial and ethnic backgrounds sit in class and think about how different diseases are more likely to affect our loved ones.

And it’s not always accurate. We must look at how environmental, psychological and social risk factors work, and try to reduce those risks. If we can reduce the risk factors, then we can reduce the number of people diagnosed.

Read more:

- Black Women and Matters of the Heart

- The Power of WE

- We Need to Protect Black Moms

- I Was Supposed to Die at 57

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jarvia Meggett, MPH, is a MSN (Entry Into Nursing) student from Charleston, SC. She earned her Bachelor’s from the University of South Carolina and her Master’s of Public Health from the University of Michigan, and is interested in women, maternal and child health among minority women.

Jarvia Meggett, MPH, is a MSN (Entry Into Nursing) student from Charleston, SC. She earned her Bachelor’s from the University of South Carolina and her Master’s of Public Health from the University of Michigan, and is interested in women, maternal and child health among minority women.

JHSON Highlights

JHSON Highlights ‘Helpful, Powerful, Kind’ Palliative Care

‘Helpful, Powerful, Kind’ Palliative Care Heart Health in Native Populations

Heart Health in Native Populations Summer Research Roundup 2023

Summer Research Roundup 2023 The Knowledge to Embrace Life

The Knowledge to Embrace Life