Nurse intuition—but with computer engineering know-how. It’s a powerful combination.

Just think about the things that exist in your life today that don’t exist in health care. A video-enabled doorbell app can text your cell phone when it’s time to change its battery. But a person whose heart would stop beating if their battery-powered medical device can’t hold a charge must rely on a paper manual and a nurse’s phone call.

Nurses who care for patients see that disconnect, and unfortunately the consequences. But empowered nurses know that they can do something to create a better way. In the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing community, faculty associate Jesus (Jessie) Casida, PhD, RN, APN-C, assistant professor Sue Verrillo, DNP, RN, CRRN, and PhD candidate Erin Spaulding are working with interprofessional teams to shape technology that will close the gaps in care.

Jessie Casida and VADCare App: the app for patients with a left ventricular assist device

A left ventricular assist device is a battery-powered device that pumps blood, surgically implanted into the heart of patients who have end-stage heart failure. It’s for patients who need a heart transplant, but if the patient is not a candidate for a transplant, they will have the device for the rest of their life.

A left ventricular assist device is a battery-powered device that pumps blood, surgically implanted into the heart of patients who have end-stage heart failure. It’s for patients who need a heart transplant, but if the patient is not a candidate for a transplant, they will have the device for the rest of their life.

Now imagine its 1995 and you’re given a paper manual and VCR videos with directions to set up a 2019 printer that will explode if you format it wrong. You have support you can call, and with time can complete the task, but it’s complicated and stressful because if you make a mistake you could die. And that’s something like the status quo for patients with a left ventricular assist device.

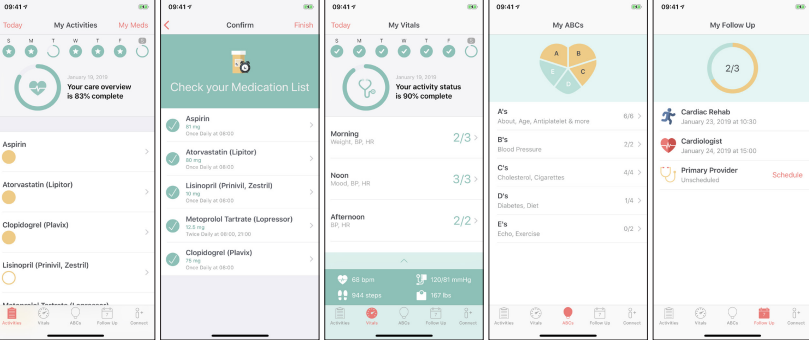

“The patients love the app, they don’t want to give it back when the trial is over,” Casida says. VADCare App is a self-management tool for patients with the device. Its prompts them to maintain the device’s functionality, helps them manage their diet, wellness, and medication adherence, lets them evaluate and report abnormal signs, and helps prevent and report complications. The app also includes a system that automatically alerts the patient’s care team when necessary.

The app is still in clinical trial, but all the signs are very promising. An Australian team’s assessment revealed that the app is superior to all other existing self-management platforms for patients with a left ventricular assist device.

Sue Verrillo and the continuous vital signs monitor, now in Johns Hopkins Hospital

Some hospital deaths are inevitable. But some are not. In the Ortho/Ortho-Spine/Trauma unit, “failure to rescue” happens when a patient dies from undetected deterioration; things like early sepsis or a postoperative pulmonary embolism, which sometimes can be predicted by vital signs.

Some hospital deaths are inevitable. But some are not. In the Ortho/Ortho-Spine/Trauma unit, “failure to rescue” happens when a patient dies from undetected deterioration; things like early sepsis or a postoperative pulmonary embolism, which sometimes can be predicted by vital signs.

Nurses in the unit take vitals (temperature, pulse, respirations, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry) every four hours, “but it’s a snapshot frozen in time,” says Verrillo. A patient’s blood pressure, pace of breath, or pulse could change at any moment—yet the numbers recorded every four hours are the ones informing clinical decisions.

Verrillo earned her DNP at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, and her DNP project was testing out the use of continuous vital signs monitors on the Ortho/Ortho-Spine/Trauma unit she managed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. She tested out ViSi, a wearable, wifi-enabled continuous vital signs monitor that records blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, ECG, posture, skin temperature, life-threatening arrhythmias, fall likelihood, and SpO2 (an estimated amount of oxygen in the blood).

The ViSi’s first 12 week trial prevented 11 deaths. The continuous vitals monitor identified early:

- Postoperative heart attacks

- Postoperative strokes

- Early sepsis

- Autonomic dysrefLexia (sudden onset of excessively high blood pressure)

- Atrial fibrillation (arrhythmia)

“It was a 73 percent drop in the complication rate,” Verrillo says. From a baseline of 22 percent down to 5.9 percent. The Johns Hopkins Hospital rolled out standard use of the ViSi continuous vital signs monitoring device on the Ortho/Ortho-Spine/Trauma unit in March 2019.

Erin Spaulding and Corrie, the heart attack recovery app to reduce readmissions

How do we prevent hospital readmissions? It’s an age-old question, and increasingly a benchmark for health care services.

One of the latest interventions to prevent readmissions for heart attack patients is an app called Corrie. It was developed for the Johns Hopkins Myocardial infarction, COmbined-device, Recovery Enhancement (MiCORE) study, with an interprofessional team from Johns Hopkins’ Schools of Engineering and Medicine, and the CareKit team at Apple. Erin Spaulding, a PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, is conducting her dissertation within the larger study.

Corrie is a smartphone app for heart attack recovery which is paired with an Apple Watch and Bluetooth enabled iHealth blood pressure cuff. Patients who have suffered a heart attack receive Corrie in the hospital and use it for 30 days following discharge. It helps them manage medications and vital signs (steps, heart rate, and blood pressure); learn about cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and lifestyle modification; connect with providers and resources to help with recovery; and develop mindfulness techniques that improve emotional strength.

Despite advances in digital health, we still don’t know much about how to tailor these devices to individual needs and better promote user engagement and health behavior change. That’s where the nurse, Erin, connects the dots. In addition to leading enrollment of participants at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, and expansion of the MiCORE study to two hospitals in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, Erin is evaluating the process of user engagement, the individual predictors of user engagement, and the relationship between user engagement and cardiac medication adherence within 30 days of discharge.

The MiCORE study is ongoing but has demonstrated promising results. In December, one of the principal investigators Francoise Marvel, MD (the other principal investigator is Seth Martin, MD, MHS) earned the Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Award for Excellence in Quality and Safety for her work leading Corrie. In October the app took second place at the American Heart Association EmPOWERED to Serve Urban Health Accelerator Competition.

“Nurses are not computer engineers, and we don’t need to be,” said Kelly Gleason, assistant professor and informatics expert, on our Pi Day podcast. “But there are gaps in care that we see first.”

Health care must catch up to today’s technology. And the nurse’s intuition, plus the engineer’s skill, the researcher’s input, the physician’s input… round out an innovative, collaborative, interprofessional team that saves lives.

This is the second in a two-part discussion of the interprofessional nursing and engineering relationship at Johns Hopkins.

Read more:

- On Pi Day, Nursing Meets Engineering

- Diverse Perspectives, Innovative Solutions

- Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Programs at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing

- PhD in Nursing

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: SYDNEE LOGAN

Sydnee Logan is the Social Media and Digital Content Coordinator for Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. She shares what’s going on here with the world.

JHSON Highlights

JHSON Highlights Heart Health in Native Populations

Heart Health in Native Populations Summer Research Roundup 2023

Summer Research Roundup 2023 The Knowledge to Embrace Life

The Knowledge to Embrace Life Summer Research Roundup 2022

Summer Research Roundup 2022