By Teddi Fine

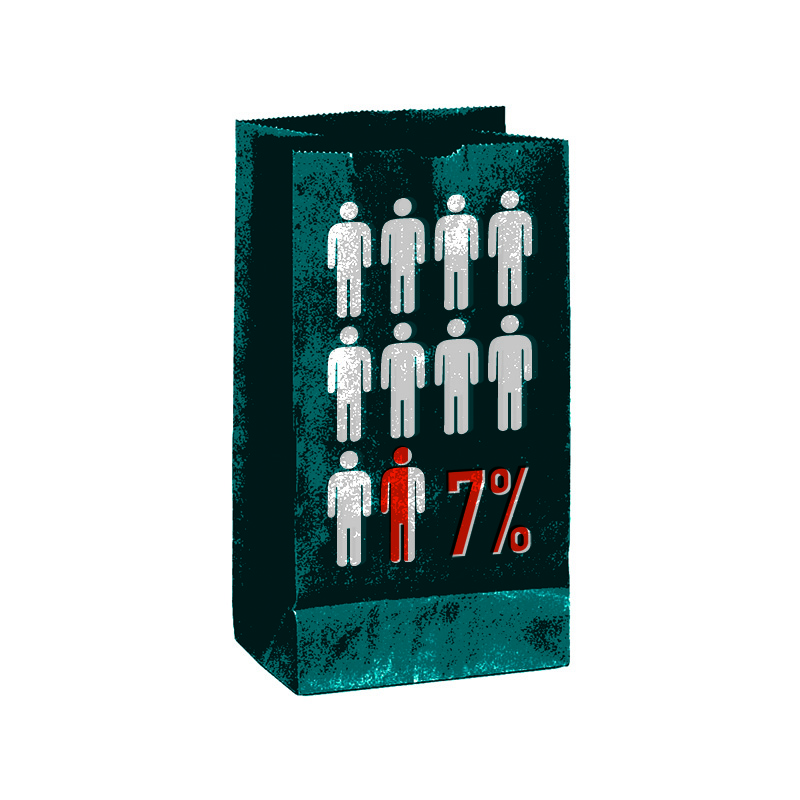

Despite chilling statistics, only around 7 percent of people who would benefit from treatment for alcohol use disorders actually get care, many staying away because of the stigma and misunderstanding associated with alcohol abuse and misuse.

In the September 2013 issue of Nursing Clinics of North America, Associate Professor Deborah S. Finnell, DNS, RN, and a colleague write a simple prescription: a brief conversation about alcohol’s effect on the brain and how the brain can heal itself almost as soon as treatment begins.

Untreated, alcohol use disorders contribute to acute and chronic health problems, lost time on the job and in school, and lost lives. They rank among the top 10 causes of disability and premature mortality worldwide. In the U.S. alone, the yearly economic toll of untreated, excessive alcohol use is estimated at $223.5 billion, or nearly $750 per man, woman, and child.

The article “Providing information about the neurobiology of alcohol use disorders to close the ‘referral to treatment gap'” describes how a one-on-one exchange or a focused video now being tested can help clarify the nature of alcohol abuse and dependence, the drugís impact on the brain, and how brain and body can both heal. An efficacy study is assessing the impact of this brief intervention on alcohol misuse and both acknowledgement of it and engagement in treatment.

Finnell has worked for over a decade to educate people about the neurobiological basis of alcohol and other substance use disorders and the plasticity of the brain. She posits that by dispelling myths and misunderstanding about alcohol use disorders, the brief education can lower barriers to care, promote recovery, and reduce the economic costs of this illness by as much as $4,000 per person per year.

It’s an intervention that she believes nurses are ideally poised to undertake, given their frequent and prolonged contact with patients. “Alcohol use shouldn’t be about shame and blame,” Finnell insists. “It’s a chronic disorder affecting the body and brain that nurses can help patients manage. Just as we educate about the pathophysiology of diabetes and hypertension, we can help people with alcohol use disorders understand and manage their illness, rather than hide from it.

And today, with many people gaining regular access to health care for the first time under the Affordable Care Act, we have an unparalleled chance to improve the quality of life for millions and lower the costs of healthcare through a brief, educational conversation.”

Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health?

Forging Policy: How Can Doulas Improve Black Maternal Health? You’re Welcome

You’re Welcome Forging Policy: Associate Dean Jermaine Monk and Education After Affirmative Action

Forging Policy: Associate Dean Jermaine Monk and Education After Affirmative Action Nursing Named Most Trusted Profession for 22nd Consecutive Year

Nursing Named Most Trusted Profession for 22nd Consecutive Year Most People Want to Breastfeed, But Need More Support To Do So

Most People Want to Breastfeed, But Need More Support To Do So