To Remove Scope-of-Practice Barriers, Nurses are Taking an Active Role in Changing Legislative Policy

by Kelly Brooks

Illustration by Mike Austin

![]() Talking health policy with her state legislator, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing student Shanna Dell ’13 feels right at home. When other families in her hometown of Madison, Wisconsin, went to the park or the movies, Dell’s family immersed themselves in political campaigning. When other families went to Disney World, Dell’s family went to Washington, DC to join in a national rally.

Talking health policy with her state legislator, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing student Shanna Dell ’13 feels right at home. When other families in her hometown of Madison, Wisconsin, went to the park or the movies, Dell’s family immersed themselves in political campaigning. When other families went to Disney World, Dell’s family went to Washington, DC to join in a national rally.

“We used to read articles and talk about issues over the dinner table as a family, and I was raised to be aware, active, and vocal,” says Dell.

And as a young nursing student, Dell is increasingly aware of how policies can have a direct impact on the work she does as a nurse and the care her patients will receive. This past winter, she enrolled in a seven-week health policy class taught by Pamela Jeffries, PhD, RN, and Rosemary Mortimer, MEd, MSN, RN. The goal of the class, says Mortimer, is for students to understand and influence policies that affect patient care and nursing practice.

And as a young nursing student, Dell is increasingly aware of how policies can have a direct impact on the work she does as a nurse and the care her patients will receive. This past winter, she enrolled in a seven-week health policy class taught by Pamela Jeffries, PhD, RN, and Rosemary Mortimer, MEd, MSN, RN. The goal of the class, says Mortimer, is for students to understand and influence policies that affect patient care and nursing practice.

The course culminated with a trip to Annapolis in February for Nurses Lobby Night, a statewide event organized by the Maryland Nurses Association (MNA). Dell and the other health policy students joined nurses from across Maryland to speak with representatives about a bill to increase penalties for patients or family members who are violent toward their healthcare practitioners. The evening was a success: the bill passed the legislature the first year it was introduced, which is “virtually unheard of,” according to Mortimer.

What did Dell and her classmates learn? “It’s important for nurses to take action. We need to stick together as a profession because there’s power in numbers, and that’s the only way we’ll make progress,” says Dell.

Nursing Practice and Policy

In the United States, there is no uniform national policy governing nursing practice. Rather, each state has its own Nurse Practice Act, a set of laws that regulate nursing licensure, accreditation, certification, and education in the state. Overseeing these laws in each state is a Board of Nursing, the governmental agency that determines who is competent to practice nursing, and what duties the nurses are responsible to perform.

When advanced practice nurses move between states, they face questions such as “Do I have the training and experience required to practice here?” or “Do I have the certifications I need to practice here?” When regulatory requirements differ, each state border represents an obstacle that could prevent nurses from practicing to the fullest extent of their capabilities, thereby limiting patient access to care.

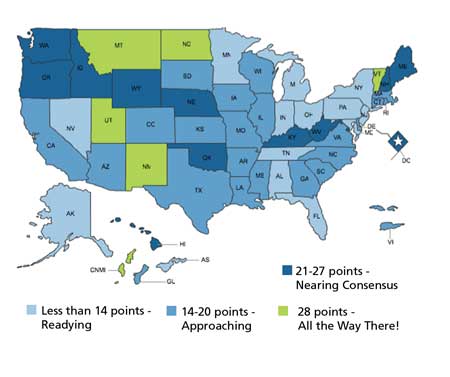

In answer to this problem, the Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRN) Consensus Work Group and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing has developed the Consensus Model for APRNs. It’s a plan endorsed by 48 major nursing associations and credentialing organizations to create common definitions, standardized education programs, fewer specialties and subspecialties, and common legal recognition across states for APRN roles by the year 2015.

The result, according to Carol Hartigan, MA, RN, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses certification programs strategist, will be that “everyone involved in healthcare—patients, their families, educators, regulators, employers, payers and APRNs themselves—will benefit from unprecedented integration and consistency in the licensure, accreditation, certification, and education of advanced practice nurses.”

Changing Policy, Expanding Possibilities

“When we talk about scope of practice, we’re often talking about advanced practice nurses, but state laws often don’t let them function to the full level of their education,” says School of Nursing associate professor, Julie Stanik-Hutt, PhD, ACNP-BC, CCNS, RN.

Stanik-Hutt is the legislative chairperson for the Nurse Practitioner Association of Maryland, a champion of collaboration among national nurse practitioner organizations, and is nationally recognized for her influence on national and state policy.

In Maryland today, says Stanik-Hutt, the most pressing scope-of-practice issue is that clinical nurse specialists (CNS) don’t have formal recognition as advanced practice nurses. As a result, there was no protection for title, no uniform definition of what a CNS does, and employers didn’t have a good understanding of what a CNS was or could do.

“I had to tell students they had to be their own marketing agents,” says Sharon Olsen, PhD, RN, who was coordinator of the Clinical Nurse Specialist track at the School from 2005–2011. “They’d apply for an advanced practice nursing position, but they’d have to help their future employers understand the depth and breadth of what a CNS could do.”

It was clear to Olsen there was a need for regulation of CNS in the state, so she started speaking with colleagues—many of whom served as preceptors for Hopkins CNS students—and said, “we really need to do something about this.”

In September 2010, the team met and founded the Chesapeake Bay Affiliate of the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. The group’s goal: work with the Maryland Board of Nursing to create language that recognizes clinical nurse specialists in the state’s nurse practice act.

“We pored over all the regulations from across all 50 states and came up with our own regulations for Maryland CNSs,” says Olsen. “We sought to make them consistent with the national Consensus Model for APRN Regulation slated to be implemented in 2015.”

The draft regulations were approved by the Board of Nursing in February 2012, and Olsen and the Affiliate Group hope to see the regulations take effect by the end of this year.

“We’re so close to finally recognizing the effort of all legitimate CNS in the state of Maryland,” says Olsen.

Scope of Practice for RNs

Scope-of-practice issues aren’t just for the advanced practice nurses; registered nurses have similar professional concerns. Take for example, patient sedation. Should RNs be allowed to administer moderate sedatives, or should that be reserved for Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists only?

In 2001, Laura Kress, MAS, MSN, RN, was invited to join a practice committee at the Maryland Board of Nursing involving the scope of practice of nurses during moderate sedation. As nurse manager of The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s endoscopy unit, an area that regularly requires administering sedation to patients, she had a first-hand understanding of the difficult questions the team faced: “What is the role of the nurse in moderate sedation? Are our nurses practicing to the highest level of our potential? Would we be stepping on any other practitioners’ toes if we move forward?”

The Sedation Committee drafted regulations—which eventually became a declaratory ruling by the Maryland Board of Nursing—allowing RNs to administer moderate sedation. In 2008, however, new interpretation of the law required the rulings to be removed, and the nurses were left without direction from the regulatory agency.

Kress is preparing to re-address the issue with the Maryland Board of Nursing by conducting a new survey of states in an effort to convince the Board of Nursing to take another look at the regulations.

Making a Difference

“I know it can sound like getting involved in legislative or regulatory efforts is terribly time-consuming and you need special skills. But that’s really not true,” says Olsen. Her advice to nurses who are thinking of joining the effort? “Just get involved!”

And the new generation of Hopkins nurses are. After attending Nurses Night, Dell found that “networking with other nurses who are politically active really showed me how you can marry political action with a nursing career,” she says. “I am not sure how it will affect my work as a nurse just yet, but I can tell you that I intend to stay involved in my professional organizations and push them to support or oppose bills that affect nurses and our patients.”

1903

A graduate of the first class of The Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Nursing in 1891, M. Adelaide Nutting helped organize and became the first president of the State Association of Grad-uate Nurses—an organization now known as the Maryland Nurses Association.

1904

Soon after the Maryland State Association of Graduate Nurses formed, a bill was put forward to form a Board of Nurse Examiners. The legislation was supported by the legislature without opposition, alteration, or amendment from the original draft and was signed on March 25. This body evolved into the current Maryland Board of Nursing.

1911

Helen Conkling Bartlett received her nursing diploma from the Johns Hopkins Hospital Training School for Nurses in 1894. She became a member of the Maryland State Board of Examiners of Nurses in 1911, and during her tenure as President (1913-1938), she successfully cam-paigned for mandatory nurses registration in the state of Maryland. In 1928 she wrote a history of the Maryland State Board of Examiners of Nurses and of the Maryland Nurses Association for its 25th anniversary.

You’re Welcome

You’re Welcome Forging Policy: Associate Dean Jermaine Monk and Education After Affirmative Action

Forging Policy: Associate Dean Jermaine Monk and Education After Affirmative Action Nursing Named Most Trusted Profession for 22nd Consecutive Year

Nursing Named Most Trusted Profession for 22nd Consecutive Year Best of On The Pulse 2023

Best of On The Pulse 2023 From the Dean: Here & Now

From the Dean: Here & Now