Compiled by Ming Tai

Since the Spanish-American war, Johns Hopkins nurses have traveled to the frontlines to provide care to soldiers and other victims of war. Through letters written home, many to the School of Nursing alumni association, these wartime nurses tell dramatic stories of providing care in less than ideal situations, and adapting to new and sometimes remote locations. The nurses dealt with extreme temperatures, high humidity, and language barriers. The spread of infectious disease was as much a threat as gunfire and grenades. But many wartime nurses also managed to find time for fun–dances, sightseeing, camaraderie.

Their letters offer a rare glimpse into the lives of the Hopkins nurses who have so heroically served over the decades on the frontlines of battle.

Spanish-American War

The first war in which Hopkins nurses served was the Spanish-American War. Here, Agnes Ysobel Irvine, 1894, writes to M. Adelaide Nutting, with apologies for her terrible scrawl as she balances the stationery on her lap from aboard the USNS Relief, August 16, 1899.

My dear Miss Nutting,

Perhaps you have forgotten that you asked me to write to you…

The Atlantic voyage was cold, rough and stormy and we had in addition to the regular staff 193 Hospital Corps men who were more or less miserable…

We had no patients until April 25 when we got 42 men wounded and sick from the 1st Reserve Hospital and that evening at 10:30 p.m. 32 wounded came from Calumpit. It was a harrowing sight. No accident case, unless from a wrecked railroad, conveys any idea of the sight.

Men covered with blood and mud; often only an under shirt and when wounded in the body, naked from the waist and dressed by N. C. men or comrades on the field with the first aid packets.

How they did enjoy the beds, the food and rest. There are no patients in the world so delightful as wounded men who have been several months on a firing line, sleeping in rice fields, in the wet with nothing but a poncho under them and broiled in the sun by day, feeding on rations and roused every night by firing and alarms.

Three men died–two shot dreadfully in the pelvis and one through trachea [sic] and lungs; the latter lived two days, the others died next morning.

The patience of the men was something to remember forever. There were no complaints, no groans. All were cheerful and bright, ready to wait to be dressed until the last and willing to help each other…

Out of two hundred and fifty men we lost three. One (from our ward) leukemia, one from dysentery and one from pyemia a day or two after we left Manila…

With remembrances to any friends and love to your own self

I am always

Yours faithfully,

Agnes Ysobel Irvine

World War I

This is a line to tell you of the death of Miriam E. Knowles [’16]. She died November 12, 1917, of hemorrhagic scarlet fever, after a five days’ illness. We had thought her only ordinarily ill up until the morning of the fifth day when we realized she was desperately ill. At 4 p.m. she died. It seems very hard to us that she should have gone through all these months of pioneer work, and be taken just as the real work commenced. She was certainly a cheerful, willing worker, her patients were all devoted to her, and she seemed to enjoy the work so much…

One thing, of course, you can assure everyone, that is she had everything done for her that was possible. There is no need of my trying to tell you what our doctors would be in a time like this; but I do want to tell you that you don’t know them as we do, nor can you ever unless you should see them under such circumstances.

As for the nurses, again you think you know them, but times like these make one realize what wonderfully fine women they are, and what they can do and will do when the stress comes upon them. It is hard, extremely hard for us all, but I feel it is only the beginning of the many things we must prepare to face–believing always that everything is for the best…

Many nurses developed a closeness to the servicemen they cared for, be they American or otherwise. Nurses spoke of the soldiers’ spirit and valor, like Virginia McMaster Foard, 1896, a Red Cross nurse in France, U.S. Base No. 1, Bellevue Unit during World War I. She wrote this in the fall of 1918.

I have been so desperately busy since coming here I have not written a letter, I am what is called a hospital teacher. I answer inquiries, etherize severely sick, wounded, or gassed soldiers and, incidentally, do all I can for anybody, such as giving flowers, fruits, “smokes” and try to ease home troubles of any nature. I visit the desperately ill, and if a long illness, write once a week to family; in case of death write to nearest of kin…

The English soldier has a smile that will not come off when he gets to an American hospital. Our men are fine. The harder they are hurt the more cheerful they are. They all get the grumps when they are neither sick nor well, but that is perfectly natural. Convalescence is a hard period, and when they get away from battle they do not think restrictions are necessary, showing a national lack of discipline. I talk to them like they were bad boys, give them a good scolding, or laugh at them. I feel so helpless, so futile, such an appalling job. I simply can cast myself on God’s mercy and ask Him to use me each day. I believe I am helping. The boys like me and often I am told I am like their mothers or aunties. You need all the tact of a woman of the world, a never failing good cheer and good humor.

Death seems so close, it certainly is “swallowed up in victory”. Immortality does not seem vague to these dear boys.

Censorship rules often led to cryptic messages. Through excerpts from letters written throughout the summer of 1917 by Claire Craigen ’19, we hear about her experiences as part of the Army Hospital No. 2 American Expeditionary Force, sent to France during World War I.

We had a most remarkably smooth passage over, thank Heaven and I have not been a bit sick… We docked last night and the enthusiastic welcome we got was worth the trip across. The people sang, cheered, shouted and we did the same. We finally ousted the band out of bed to play the national airs and the place went mad. We all cried

We are in the country about a mile from the railroad station and a five minutes walk from a tiny village… The people seem so glad to see us…

The outside of our building was decorated with the flags of all nations including a huge United States one… New censor rules have just been read and it seems if anything I write should get into print at any time I would stand in danger of being shot at sunrise, which I am not quite ready for.

We shall probably leave this place in a day or two when I believe we are really going to the “front”. When I get a chance I will write again from there (wherever it may be).

…. We have a hero in our midst. One of the men of a nearby training camp was practicing throwing hand grenades. Took the plug out and was about to throw it when someone appeared in every direction he could throw it. He consequently held it and had his hand blown off. By comparison, one of the men was shot in his hand during the night, wound supposed to have been self inflicted to prevent his being sent to the trenches.

World War II

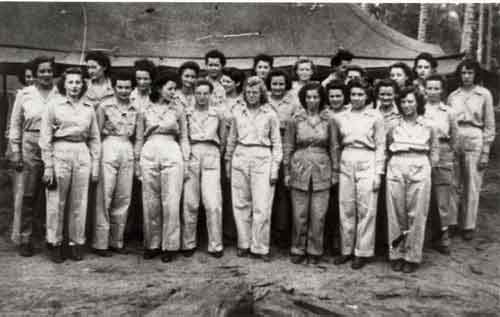

Those in General Hospital No. 18 traveled to Australia, the Fiji Islands, and New Zealand. Elizabeth McLaughlin, ’37, talks about her experiences in Fiji, where the unit treated patients in a converted school, May 1943.

A year ago the 18th General Hospital was in San Francisco preparing for embarkation. After that voyage and two months in New Zealand, we are chalking off nine months on this island… In these months our hospital has developed and matured, and now we have the “dug in” feeling of a certain permanency. Long settled down to a busy routine, perhaps what was once novel has become the commonplace. We are acclimatized and accustomed…

When you think of us at work here, do not picture us as doctors and nurses only. Working along with us is a group of real soldiers who make up our detachment of men. A great part of whatever success we may have is due to this band of men who cast their lot over a year ago in Fort Jackson with a group of bewildered Army rookies fresh down from Baltimore. The officers and nurses, in the difficult and abrupt transition from civilian to Army life, found loyal and willing hands in the group assigned from the 56th General Hospital. We will not soon forget how these men began at once the hurried preparations to get this “cadre” overseas…

No. 118 took a similar route, traveling to New Zealand, Australia, and the Philippines. Helen J. Weber ’34 sent frequent correspondence to the alumni association, keeping it abreast of her work. In this letter dated August 14, 1943, she speaks of adapting to the new environment.

After three months in our new hospital, there are things to tell you about it.

Situated on a fairly flat acreage, the buildings are set in a fine grove of trees. Tall gums, rugged iron barks, slim tea trees, and even a red mahogany here and there, lend both shade and beauty to our Post…

The nursing staff was spread very thin over the wards in the beginning, but, shortly after we moved, an entire Station Hospital group was attached to us for temporary duty. Still later, in July and again in August, we received casuals from the States–some on temporary duty others permanently attached…

I wish so much that you could be told of our greater problems, but that is the very thing that cannot be written. There are certain aspects of medicine that we see here that are not seen at home, and these create problems for physician, nurse, and finally even administration (how to discharge a patient to the benefit of the army without detrimental effects to the individual). But these are problems which must be saved for discussion when we return.

We have been cold. In buildings with a single inch and a half thickness of wood for floor, walls and ceilings, there is little protection from temperatures which have dropped at least once to 24 [degrees] F. and range each morning in the thirties and forties. The dampness of a wet season has not helped. This is not a complaint but merely a statement of fact; elsewhere, units have lived in the inconveniences of tents, lived with malarial surroundings, ducked into air-raid trenches, and suffered under tropical heat and humidity–our minor tribulation just happens to be cold.

We have learned to cope with it…

Since our move, we have opened our Officer’s Club and have had many a pleasant social evening together, sometimes real parties with dancing and party fare, other times just impromptu get-togethers for ping-pong, sings, outings of some sort. Some of us own horses that are boarded in a nearby dock; others of us have bicycles on which we explore the surrounding countryside. We enjoy our off-duty time…

The war news looks so encouraging, doesn’t it? Right now the whole Pacific is marking time until that day arrives when there will be expanded activity, and every day’s progress in Europe seems to bring that day closer to us. We all talk about that and about coming home when it’s all over!

Although the primary reason nurses went to the frontlines was to care for patients, it wasn’t always all work and no play, as detailed by Mary Claire Cox ’35, who writes from “somewhere in North Africa”, in July 1943.

…We’ve been overseas for seven months; came in the first convoy from the States after the invasion.

We have a wonderful set-up here. It is a beautiful spot by the sea. We are lucky enough to live in houses and our hospital is also housed. The beach is just out our back door so, of course, we go swimming every day and are brown as berries.

I have charge of a very large septic surgery ward and up until a month ago we were busy as could be, working overtime more often than not…

Our patients have arrived to us in surprisingly good condition, their wounds cleaner than would be expected, and far fewer in shock than we were prepared for. Keeping up with sterile dressings is my main headache. We do as high as thirty dressings per day so we have to keep our patients busy folding bandages. They are very good to help out. Our equipment is pretty good although at first we had to use our ingenuity to improvise for what we did not have.

Our social life is not neglected. We have our moments of leisure. We have a nice officers’ club which sponsors a weekly dance as well as Bingo once a week. The A.R.C. does its bit by putting on three movies a week.

Our food is G.I. and pretty drab, but we supplement it with fruits, melons, vegetables and eggs from the village. All of our water is chlorinated and tastes terrible.

The climate here is hot but no hotter than the south where I grew up. There is always a cool breeze, and the nights are chilly enough for a light blanket.

For our work uniform, we wear blue seer-suckers. We do not wear caps because of the mosquito netting on all the beds, making it impractical to do so. We do not wear hose as we can’t get them. Some of the girls wear white ankle socks. We are not allowed to wear civilian clothes at all…

Vietnam

… I was assigned to the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Republic of Viet-Nam, located in northwest Saigon. The Air strip services both the military base and the civilian airport for Saigon. I arrived in Saigon December 17th, 1968….

The greatest time of my tour was involved in the care of the military men. The military medical system in the Combat Zone is the finest in the world. The wounded man is given immediate first aid in the field by the Medic and evacuated by helicopter to the nearest Army Field Hospital, usually arriving within 10-15 minutes after injury, for initial surgery and care by hard-working teams of Army Physicians, Nurses and Medical Technicians working round-the-clock. As soon as he is able to be moved, he is brought by ambulance bus to the Aeromedical Evacuation Plane and flown to one of the three Casualty Staging Hospitals for evacuation to the States…

My first months I cared for the Combat Casualties. We received them from the In-Country flight, changed their dressings, gave them baths and shaves, fed them and after a nights’ sleep sent them on their way. The rest of my tour I was in charge of the 30-bed Dispensary Ward caring for Base Personnel and those passing through Tan Son Nhut with general medical illnesses or minor injuries. More serious problems were cared for at the Army 3rd Field Hospital in Saigon or Air-Evacced to Cam Ranh Bay…

We worked hard and our work week averaged 60 hours, many of them were 72 hours. This did not leave too much spare time. Each of us had to find our own way to pass the long year away from home and loved ones. We read, listened to the Armed Forces Radio-TV, and mostly revived the lost art of conversation. As time permitted (and also security–we were restricted to base after 10 PM and during periods of increased guerilla activities around the base and in Saigon) we took brief trips into Saigon…

My most treasured memory of my tour in Viet-Nam is of the valor and courage of our American Servicemen–their selflessness, comradeship and brotherhood. My special favorites were the Enlisted men and Officers of the 377th Security Police. I became the “Mom” to the 368 men guarding the base perimeter at night. Every night, I would wave them off to work either perched on this Rat Bait Box outside my room or from the 2nd floor veranda, sometimes with the help of other Nurses or WAF. My sons would ride by in their trucks, jeeps, tanks or Armored personnel Carriers in fair weather or Monsoon rains to protect us… On Mother’s Day they presented me with a beautiful bouquet of pink gladioli on their way to work. One night they surprised me by naming one of the mini-gun tanks after me…

Desert Shield/Desert Storm

During Desert Shield/Desert Storm, army nurse Captain Nancy Woods, PhD ’04, serving with the 86th Evacuation Hospital at the King Khalid Medical Center (KKMC) in Saudi Arabia, wrote to her husband often. The letters didn’t have far to go. A major in the Air Force, John Woods was also serving in Saudi Arabia with the 101st Airborne Division.

My Dearest John, 20 January 91

I hope you are safe and well. I don’t know where you’re at now, but I pray daily for your safety.

We spend most of our time in MOPP 2 and are taking our nerve agent pretreatment pills. Ever since the 16th, we’ve had lots of scud alerts and have spent a fair amount of time in MOPP 3 & 4. I think the hardest time is when the air raid sirens go off and we have to take cover–that waiting for something to happen seems to last forever. Last night we had to go to black out also. Really eerie.

We hear the planes flying over a lot now. That’s how we know the war had started–we were lying around in the ER and heard all the planes!

We heard about the scud fired at Daharan! I worried about you, honey! We had 2 fired at KKMC. Thank God for those patriots! We’re all encouraged by the success of the air force and hope they continue! It was alarming to hear about the scuds fired in Tel Aviv. I wonder where all this will go.

We haven’t seen any combat injuries–unfortunately, I know that will come. We get lots of orthopedic injuries–people fall as they run to get cover, etc! We’ve also had some self-inflicted wounds (gun shot). Some of these soldiers are so young and so scared… But I love taking care of these soldiers. It’s nice to make a difference!

I hope we’ll do good when the casualties come in. I can’t imagine the types of injuries we’ll see…

While letters from earlier wars took weeks to arrive in the States, technology today allows for those on the frontlines and surrounding areas to send home instant and uncensored reports. In this e-mail message from fall 2004, Jillian Murphy, Accelerated ’04, writes to school faculty member Jo Walrath about her work as part of the Sharana Provincial Reconstruction Team in the Paktika Province in Afghanistan.

Hi Jo,

Just a quick note from Afghanistan. I’m doing fine–still a little culture shock and adaptation going on. I’m living in a tent in a mud fort in a high valley in the border province of Paktika–the home of the Taliban. The battle for the hearts and minds is on here. We’ve lost a few soldiers within about 50 miles of me in the last week. But so far I haven’t felt too unsafe. A little uncomfortable in one village where we were assessing a school site and there was a guy that we think was Taliban who disappeared suddenly. But nothing happened. The most dangerous thing that has happened to me was when our own guys fired a Mark 19 (grenade launching big gun in a turret) at me which landed the grenade about 100 yards away. That’s enough to get your pulse rate up. No injury, though I was more than a little annoyed. Not to mention the Afghan soldiers I was with who wanted to fire back… nearly an international incident and bloodbath. But we diffused it…

The medical situation here is pretty grim. I can’t treat people when I’m out on missions because it’s just not in my lane. I can only get the village on the surgeon’s cell list. I’m going to try to go on some of their missions though. We won’t be doing much until after the elections though. Things are getting too dangerous. The bad guys are getting gutsier and we have to work to stay ahead of them.

So I’m attaching a picture of me at one of the schools we are working on. I’m with my team. How are things at Hopkins?

Jill

Love, Honor, and Courage

Love, Honor, and Courage Take Action!

Take Action! The Anatomy of a Hopkins Nurse

The Anatomy of a Hopkins Nurse