Nurses Are Vital in Developing New Health Information Technologies

By Stephanie Shapiro | Illustration by Andy Lackow | Photos by Chris Hartlove

Gail Robel, BSN, RN-BC, became a nurse 25 years ago when paper charts were routine and few could imagine entering a patient’s vital signs into an electronic database. But Robel, an analytical thinker, quickly recognized information technology’s enormous potential for raising the quality of healthcare.

Early in her career Robel gained IT expertise in bits and pieces. As a nurse manager on a labor and delivery unit in a New Jersey hospital, she designed templates for recording data and mastered Microsoft Excel® for computerizing patient information. At the time she didn’t even know that her work had a name. “I was doing the best I could to streamline workflow without knowing what informatics was all about,” Robel says.

Robel would discover that she was among a growing number of nurses and other clinicians across the country determined to harness the power of health information technology in the search for solutions to chronic healthcare-delivery problems. With their foresight a new era of safe, patient-centered care built upon powerful, interoperable computer systems, sound data, and innovative research methods had quietly begun to take shape.

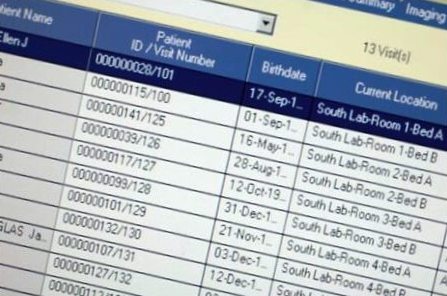

The new healthcare-delivery model revolves around the electronic health record (EHR), a one-stop documentation system that fosters safer handoffs, communication between providers, informed decisions, accurate discharge plans, and other benefits. Aggregated across multiple healthcare organizations, patient data can serve to pinpoint important healthcare trends and spawn system-wide ideas for cutting costs, improving efficiency, and managing chronic disease.

Nurses like Robel, a recent graduate of the new applied health informatics program offered online by The Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, remain indispensable to healthcare’s electronic makeover. Now the clinical systems coordinator at San Juan Regional Medical Center in Farmington, New Mexico, Robel is developing an electronic documentation system according to basic nursing principles.

“I want my EHR to be streamlined, to be cognitively simple, and I want it to deal with the patients’ priorities,” she says.

Without nurses’ input, no health information system would be complete, says Stephanie Poe, DNP, MSN ’92, RN ’78, who last year became the first Chief Nursing Information Officer at Johns Hopkins. “Nurses are the largest workforce that is most consistently at the bedside and so we have intimate knowledge of the impact of IT on patient care,” Poe says. “Because technology is so tied to people’s workflow, it is critical to have all clinicians, including nurses, involved in the selection, design, implementation, training and the evaluation of these electronic health records.”

Nurses Join the Tech Team

Since the 1950s, nurses have pioneered the use of patient data to enhance the quality of care, an endeavor that gave birth to the discipline of nursing informatics. As technological capability expanded, so did nurses’ ability to find data-driven solutions to workflow logjams, safety flaws, and poor continuity of care.

Confident that health information technology (HIT) would soon transform healthcare delivery in every imaginable setting, nursing informatics organizations gathered to lay the groundwork for electronic systems that were patient-centered and attuned to clinical workflow. Meeting with peers across disciplines, they established standards for the design of information systems, the selection of core data for documentation, and appropriate electronic formatting.

In 1999 support for HIT intensified when the deadly toll of chronic safety problems and quality shortfalls were chronicled in To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, published by the Institute of Medicine. Two years later another IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, highlighted information technology’s capability to fix the broken health system, giving another push to the adoption of electronic health records.

The transition to electronic documentation didn’t start in earnest until 2009, when the federal government waved an enticing carrot (and menacing stick) at the healthcare community. As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act earmarked $19 billion for HIT education and development.

The Act also set a 2015 deadline for developing systems that adhere to “meaningful use” standards for providing complete and accurate information, greater access to data across health systems, and portals where patients could see their medical records. By meeting those measures as they take effect in three, increasingly stringent phases, eligible providers and hospitals can qualify for substantial Medicaid and Medicare bonuses. Penalties await those who don’t.

Implementing these policies requires that nurses be fully involved in the design of a nationwide health information technology infrastructure. And they’re up to the challenge. Members of the Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) Initiative—an alliance of more than 20 nursing and nursing informatics societies—have made recommendations for fostering digital literacy and patient-centered technology. And the Alliance for Nursing Informatics teamed up with the American Nurses Association to promote the integration of standardized nursing terminology in all electronic systems designed to meet meaningful-use standards.

In designing documentation systems, nurses provide a counterbalance to health industry vendors and institutions preoccupied with the financial implications of meaningful

use, says Carol J. Bickford, PhD, RN-BC, a Senior Policy Fellow for the American Nurses Association. She argues as well that meaningful-use regulations should make room for narrative: the patient’s story, thoughtfully handwritten by nurses for generations.

“We’re the coordinators of care. We’ve got a sense of the patient,” Bickford says. “We’re participating with patients and strategizing how to help them stay well. Our perspective is the whole person, which informatics, alone, can’t capture.”

The groundbreaking report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, published last year by the IOM and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, concluded that healthcare reform can only happen with nurses as full partners in the decisions that drive reform. And that includes those that concern data collection and electronic information systems. As important, the report suggested, was the understanding that nursing practice would eventually hinge on IT’s ability to manage information, improve workflow, and give clinical support as flawlessly as possible.

“You can never program out all errors,” says School of Nursing associate professor Patti Abbott, PhD, RN, who has gained a global reputation as a vocal HIT advocate and watchdog in a field teeming with competitive interests. “What you can do is build a system that supports the way people think and the way people work and help them not make the error in the first place,” she says.

Tomorrow’s Tech-Savvy Nurses

As the transition to a HIT-managed health system is underway, Abbott anticipates a soaring demand for nurses with advanced informatics skills. Despite the surge of nurses entering the informatics field, some 50,000 positions remain vacant. Nursing education can only meet the need with a major and speedy overhaul, Abbott says.

Spurred by the HITECH Act, accrediting organizations and professional associations are developing strategies for cultivating new generations of tech-savvy nurses. Both the National League for Nursing (NLN) and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) have made HIT competency a requirement in all baccalaureate nursing curricula.

A $1.8 million HITECH grant has also enabled Abbott to develop a DVD, an inexpensive and portable tool for learning how to achieve meaningful-use requirements. Abbott’s lessons come with a hands-on opportunity to practice on an electronic documentation system developed for the Veterans Administration Healthcare System. “Students can listen to a lecture, and then they launch the DVD. There are a series of exercises that teach them how to work with HIT based on the specifics of meaningful use.”

Using federal grant money, the School of Nursing also launched an applied health information certificate program in 2010. Even Abbott was surprised by the enthusiastic response. This year the distance-learning program drew 83 applicants for 13 slots in the incoming class.

Before she enrolled in the certificate program last year, Robel had no formal informatics training other than a few seminars sponsored by the American Nursing Informatics Association (now ANIA-CARING). Mostly she learned on the job, using emergency department charting software, performing medication reconciliation, and doing occasional coding.

The certificate program coincided with her work in New Mexico coordinating the launch of an EHR system tailored to the hospital’s 10 outpatient clinics. Abbott’s course on HIT usability in particular, “fit in perfectly with everything we’re going to be doing,” Robel says.

While vetting vendor proposals for EHR systems, she heeded Abbott’s advice for creating an information system that flowed seamlessly between the various outpatient clinics and the hospital itself. “When a patient we see in a family clinic comes to the ER, or has to be admitted, we want to be sure that his record, with a list of medications, allergies, and past medical history, is readily available,” Robel says.

Working closely with information technicians, Robel’s clinical perspective has been essential to building a documentation system that is truly usable. “My experience allows me to have an understanding of healthcare workflow and the need for common language that technicians don’t have,” Robel says.

She often serves as a mediator who finds middle ground between clinicians’ need for an intuitive electronic records system and the technicians’ more pragmatic approach to programming. For example, if too many clicks are required to document or access data, clinicians will become impatient and perhaps omit important information. When these conflicts arise, Robel strives for a compromise amenable to all.

Robel, 57, loves the dynamics of change and savors challenges such as figuring out how to get the EHR to interface with the Computer Provider Order Entry system. She gives frequent pep talks to less enthusiastic clinicians loyal to paper charts and daunted by the complexities of migrating to an electronic information system. “One of the biggest challenges in getting the EHR off the ground is reluctant nurses and doctors,” she says. “Many are retiring because they don’t want to do it. It is a challenge.”

Meeting the Challenge

At Johns Hopkins, Poe made a point of engaging all nurses in preparation for a system-wide shift to electronic medical records that is nearly complete. “We found that changing from paper-based systems to a computer-based system is more than just a physical change in the way you do things. It is a transition that elicits a mix of emotions as people realize that the way they have been doing their work for ever and ever will change dramatically.”

Mindful of the emotional obstacles to change, Poe created a peer coach program for training bedside nurses on nine units in the use of electronic health records. Once nurses completed an introductory class, they were led by coaches through continuing training activities specific to their clinical area.

Coaches also monitored calls to the IT Help Desk to identify recurrent questions, and created survival guides and tip sheets to address persistent trouble spots. Staff members were tested for their competency in using the new system, and received remedial training if they failed. As the documentation system went live, coaches offered refresher courses and continued support. The program boosted confidence and competency, Poe says.

In building a web of nursing support and expertise across the hospital, Poe has also created the framework for bringing all nurses into the digital age. As Johns Hopkins Medicine progresses toward an enterprise-wide patient medical information system, nurses cannot take for granted their role in the re-engineering of healthcare.

“Nursing must take a strong leadership role in ensuring that nurse-sensitive issues are on the radar,” Poe says. “And we need to do more research to determine what we really need to document and what is just extraneous or doesn’t give us or the patient a benefit.”

Breaking the Mold: Alumni Talk with Mirini Kim

Breaking the Mold: Alumni Talk with Mirini Kim Nursing’s Tech Team

Nursing’s Tech Team Interprofessional Then

Interprofessional Then The Case for Space: The Nursing Shortage and the Overcrowding of the U.S. Nursing School

The Case for Space: The Nursing Shortage and the Overcrowding of the U.S. Nursing School The Alcohol Question

The Alcohol Question