By Kelly Brooks-Staub

Hopkins Nurses draw inspiration from nursing’s past-heroes such as Florence Nightingale, Clara Barton, and Margaret Sanger-and continue their legacy of nursing excellence.

The Pathfinders

In 1998, Fannie Gaston-Johansson, PhD, RN, FAAN became the first African-American woman to earn a full professorship with tenure at the Johns Hopkins University. And in 2001, she became the first female dean of any program at Gšteborgs Universitet in Gšteborg, Sweden. Like Mary Eliza Mahoney (photo inset), who became the first black RN in the U.S. in 1879, Gaston-Johansson is both a groundbreaker and champion for minority populations.

In 1998, Fannie Gaston-Johansson, PhD, RN, FAAN became the first African-American woman to earn a full professorship with tenure at the Johns Hopkins University. And in 2001, she became the first female dean of any program at Gšteborgs Universitet in Gšteborg, Sweden. Like Mary Eliza Mahoney (photo inset), who became the first black RN in the U.S. in 1879, Gaston-Johansson is both a groundbreaker and champion for minority populations.

What advice does Gaston-Johansson have for today’s minority nursing students? “Explore new ideas, places, and cultures. This will help you better appreciate the people you care for and become a strong leader in the complex world of nursing.” Gaston-Johansson hopes to be remembered by future nurses not only for being a “first” at Hopkins, but also for her work on pain measurement and assessment, international research, and mentorship of young nursing students and faculty.

The Globe Trotters

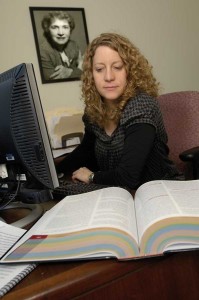

After graduating from the Johns Hopkins Training School for Nurses in 1906, Vashti Bartlett (photo inset) worked for two years at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and then began a career in global nursing. Her travels took her around the world to Newfoundland, France, Belgium, Russia, Manchuria, and Haiti. Today, alumna and faculty member Nancy Glass, PhD, MPH, RN shares Bartlett’s passion for providing care in remote, underserved regions of the world.

After graduating from the Johns Hopkins Training School for Nurses in 1906, Vashti Bartlett (photo inset) worked for two years at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and then began a career in global nursing. Her travels took her around the world to Newfoundland, France, Belgium, Russia, Manchuria, and Haiti. Today, alumna and faculty member Nancy Glass, PhD, MPH, RN shares Bartlett’s passion for providing care in remote, underserved regions of the world.

First introduced to nursing in the early 1990s while working as a Peace Corps volunteer in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Glass is now an associate professor of nursing and serves as an associate director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

She has started several projects in the Congo, which has been ravaged by war since her days in the Peace Corps. “When I was there at the age of 21, I had no specialized skills or knowledge. It’s wonderful to be back 18 years later, having been trained in a way that allows me to make a real contribution.”

The Change Makers

Margaret Sanger [photo inset] headed a crusade to legalize birth control and she founded the American Birth Control League, which later became Planned Parenthood,” says Hayley Mark, PhD, MPH, RN. “Without her work, I would not be able to do mine.”

Margaret Sanger [photo inset] headed a crusade to legalize birth control and she founded the American Birth Control League, which later became Planned Parenthood,” says Hayley Mark, PhD, MPH, RN. “Without her work, I would not be able to do mine.”

In the early 1900s, Sanger was outspoken and relentless in her fight against obscenity laws that made giving out information on contraception a crime. A century later, Mark conducts research and disseminates information on sexually transmitted disease with the goal of helping women make better decisions about their sexual health.

“Sanger paved the way for my research with her devotion to putting information and power in the hands of women and her insistence that everyone has the right to control their own lives,” says Mark. “I hope that my work also empowers people through information, helps them make the best decisions for themselves, and chips away at the stigma surrounding sexual health care.”

The Educators

The second superintendent of nurses at Johns Hopkins, Mary Adelaide Nutting [photo inset], was a strong advocate for nursing scholarship,” says Stephanie Poe, MScN, RN. “She devoted much of her life to nursing education and teaching nurses to think critically.”

The second superintendent of nurses at Johns Hopkins, Mary Adelaide Nutting [photo inset], was a strong advocate for nursing scholarship,” says Stephanie Poe, MScN, RN. “She devoted much of her life to nursing education and teaching nurses to think critically.”

Poe, along with colleagues Kathi White, PhD, RN, CNAA, BC and Sandra Dearholt, MS, RN, is the author of Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines. “Evidence-Based Practice is all about critical thinking,” says White. “Nurses examine their current practices, and then critically evaluate available research to determine the best course of action. It’s all about making good decisions based on evidence.”

Nutting, who helped found the American Journal of Nursing in 1900, felt that disseminating best nursing practices through professional journals was necessary to the development of nursing as a profession. Today, using the EBP Model, bedside nurses have a way to tap into other nurses’ discoveries and incorporate them into their everyday practice.

“Our work provides a way for nurses to find research and evidence and critically evaluate it,” says Dearholt. “One hundred years from now, I hope that EBP will be commonplace, and that our publication will have been a historic milestone along that path.”

The Researchers

After earning her master’s degree in psychiatric nursing, Deborah Gross, DNSc, RN, FAAN, began working with mentally ill patients in a children’s hospital. “I became disillusioned there,” says Gross. “I saw children hospitalized for months on end and therapists who were not held accountable for the health of the children.”

After earning her master’s degree in psychiatric nursing, Deborah Gross, DNSc, RN, FAAN, began working with mentally ill patients in a children’s hospital. “I became disillusioned there,” says Gross. “I saw children hospitalized for months on end and therapists who were not held accountable for the health of the children.”

Gross decided to leave the field of psychiatry, but rediscovered her passion when she started working with parents to prevent future mental illness in young children. That strategy built upon the discoveries of Hildegard Peplau (photo inset), a nursing theorist known as the “mother of psychiatric nursing.” Her 1952 book emphasized the importance of nurses and patients collaborating to create a shared experience of healing and therapy.

“Peplau’s work taught us to honor the nurse-patient relationship,” says Gross. “Clients are not passive, and our best results come out when nurses collaborate with patients. We can work together to ensure happier, healthier lives for young children.”

The Artists

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all dark night – some are so young;

Some suffer so much – I recall the experience sweet and sad…

Thus wrote Walt Whitman (photo inset) in his poem, The Wound-Dresser, in 1865. As a volunteer nurse during the civil war, Whitman worked with wounded and dying soldiers in more than 40 hospitals. His experiences there profoundly changed his world view and provided fodder for his later writings.

Ron Noecker ’07, a pianist, vocalist, and oncology nurse at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, can relate. Last year, he produced a CD entitled Healing Songs at Christmas, an album dedicated to people living and working with cancer. “Music is a form of expression of the feelings I have for my patients, people going through all kinds of ordeals,” he says. “Artistic expression-music, painting, writing-is a way to meditate on that. For me, playing music is an avenue to find my way to acceptance.”

The Innovators

When Anna Wolf [photo inset] returned to Hopkins in 1941, she took on a dual role as director of the nurse training school and chief nursing officer in charge of the hospital nursing service,” explains Karen Haller, PhD, RN, FAAN, vice president of nursing and patient care services at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. “Today, it takes two of us-Martha Hill and me-to do what she alone managed!”

When Anna Wolf [photo inset] returned to Hopkins in 1941, she took on a dual role as director of the nurse training school and chief nursing officer in charge of the hospital nursing service,” explains Karen Haller, PhD, RN, FAAN, vice president of nursing and patient care services at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. “Today, it takes two of us-Martha Hill and me-to do what she alone managed!”

In 1941, Wolf was the best-educated and most seasoned administrator to run the nursing program in its history. She pushed for a university-based nursing program at Hopkins, and, according to Martha N. Hill, PhD, RN, FAAN, Dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, “we have continued to champion university-based education for our frontline nursing staff and graduate education for the many advanced-practice roles that exist today.”

With degree options including a PhD, DNP, MSN, MSN/MPH, MSN/MBA, and more, today’s Hopkins nursing students have ample opportunity for advanced nursing education. “Wolf may not have envisioned this evolution in nursing practice and education, but she set us on the path,” says Haller. Hill agrees, “We are working hard to carry forward her legacy.”

The Detectives

Cherry Ames (photo inset): nurse, traveler, mystery-solver. Between 1943 and 1968, Cherry was the main character in 27 mystery novels that took place in hospital settings across the country. Think of the series as the nursing equivalent of Nancy Drew.

Cherry Ames (photo inset): nurse, traveler, mystery-solver. Between 1943 and 1968, Cherry was the main character in 27 mystery novels that took place in hospital settings across the country. Think of the series as the nursing equivalent of Nancy Drew.

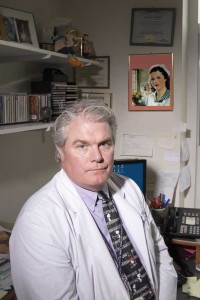

“I was more of a Hardy Boys fan myself,” admits Dan Sheridan, PhD, RN, FAAN when asked about the Cherry Ames books. “But I did always love a good mystery.”

Perhaps that’s what makes him one of the nation’s foremost forensic nurse investigators. “Sometimes, the work is like CSI with high-tech tools and blood and guts,” says Sheridan. “Other times, it’s reviewing paperwork, interviews, and depositions. To solve the mystery of what really happened to your patient, you must go through the evidence in detail and use deductive reasoning.”

Like Cherry Ames, Sheridan can often wrap up a case, satisfied with the story’s conclusion: “I feel good about my work-I get to help keep patients who have been victimized be safer and prevent further abuse.”

Hands & Words Are Not For Hurting

Hands & Words Are Not For Hurting Mentoring Moms

Mentoring Moms Jhpiego Assists Lesotho to Strengthen Nursing Education

Jhpiego Assists Lesotho to Strengthen Nursing Education